The Broken Land

“The Broken Land,” “Man on Fire,”

“Loss,” “Three Short Stories About Death”

X-Men Red #1-4

Written by Al Ewing

Art by Stefano Caselli (#1-3), Juann Cabal, Andrés Genolet, Michael Sta. Maria (#4)

Color art by Federico Blee

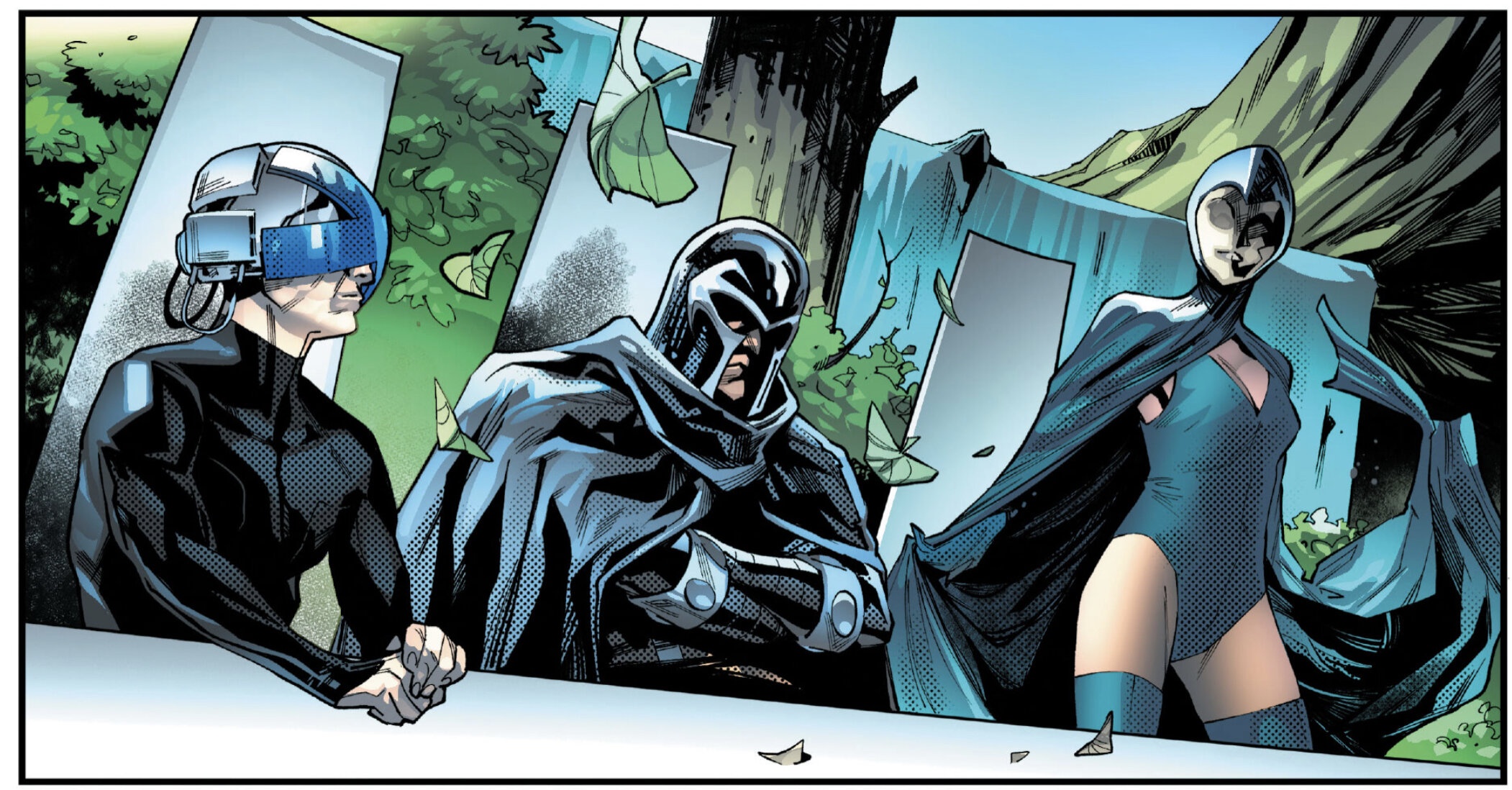

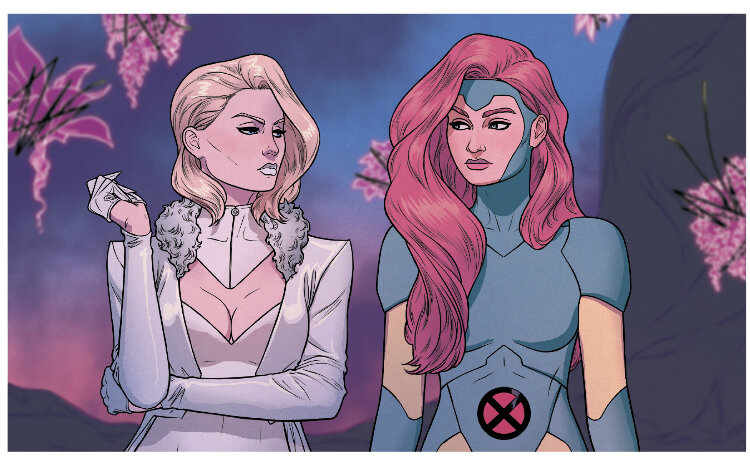

X-Men Red is a very bold and new kind of X-Men series, one with a premise that would have been entirely inconceivable prior to 2020. This is the series exploring the culture of the Arrakii mutants introduced in X of Swords, who now reside on a terraformed Mars that has been declared the capital of the solar system without consulting with any of the humans who happen to live there. Storm has emerged as the Regent of Arrako, and is the first Earth mutant to become part of the Great Ring, the Arrakii equivalent of the Quiet Council. She remains on that council, though Magneto has quit to take up residence on the red planet. Sunspot is also living on Arrako and appears to be gradually working towards some personal agenda, and Cable is there along with Abigail Brand, continuing on from where Ewing’s previous X-Men series SWORD left off. (Whoops, sorry, I meant to write about that after it concluded but never did. It was mostly very good.)

Ewing spends some time developing the members of the Great Ring, but the book is really about the Krakoan mutants and how they adjust to living with totally different customs and the question of how much they should attempt to shape the future of a people they have no history with.

Sunspot initially seems the most eager to bring a bit of Earth culture to Mars, but it’s his way to play dumb while gradually working towards something bigger in plain sight. He and Brand are the mutants with the widest perspective – his experiences with the Shi’ar make him think on a galactic scale. But while Sunspot sees a universe full of opportunities, Brand can only see a great game of grim intergalactic politics and is plotting to decrease the wider influence of both Arrako and Krakoa.

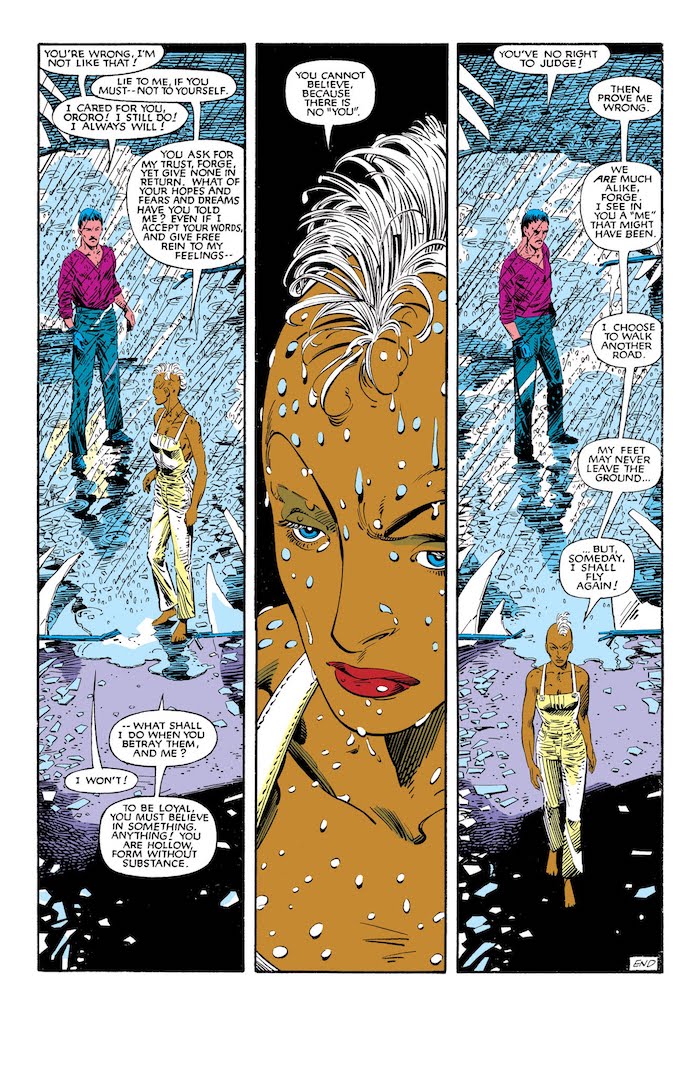

Storm, always a person of great integrity, rejects her regal trappings and finds herself reliving the time she defeated Callisto in battle and took on leadership of the Morlocks but on a far grander scale. Practice has not made it any easier, and she seems to be so occupied by maintaining her credibility and spinning the plates of her many responsibilities that she can’t devote enough time to figuring out exactly what the now overtly evil Brand is up to.

Magneto, on the other hand, comes to the red planet utterly humbled and broken, and finds himself accidentally accruing power and joining the Great Ring after defeating Tarn the Uncaring, the Arrakii’s answer to both Hitler and Mengele, in a duel. This story, which plays out in the third issue, is where Ewing makes it clear what kind of series he’s writing. It’s brutal and thrilling, and one which constantly tests the mettle of its leads. Magneto’s triumph over Tarn is one of the most exciting things I’ve read in a superhero comic in years. Ewing and Stefano Caselli pace the sequence masterfully, leaving room for suspense even after Sunspot uses Isca the Unbeaten’s power to never lose against her in order to make Magneto’s victory a foregone conclusion. Tarn, one of the best new mutant X-Men villains in years, had already been developed by Zeb Wells in Hellions and Ewing in SWORD, so his loss carries weight particularly in light of the Arrakii’s rejection of mutant resurrection. It hard to be Tarn for this plot beat to work – someone formidable, endlessly cruel, and already established to be the most hated man on Arrako.

At the end of the third issue Ewing positions Magneto not just as a member of the Great Ring, but as a hero to all Arrakii for slaying Tarn. By the end of the fifth issue – which I’ll write about later on – circumstances shift power to Magneto’s seat on the Ring. It seems to me that Ewing is gradually writing a story in which Magneto gets to live the dream of his younger self as a beloved leader on an entire planet of mutants, but it’s all cursed. As we move ahead with this series it seems that the tension will be the question of what happens as Magneto acclimates to power in this world, and how it may pit him against his allies Storm and Sunspot. It looks a lot like Ewing is slowly building a situation in which Magneto may actually find himself in direct conflict with Charles Xavier and the X-Men, but in a totally fresh way.

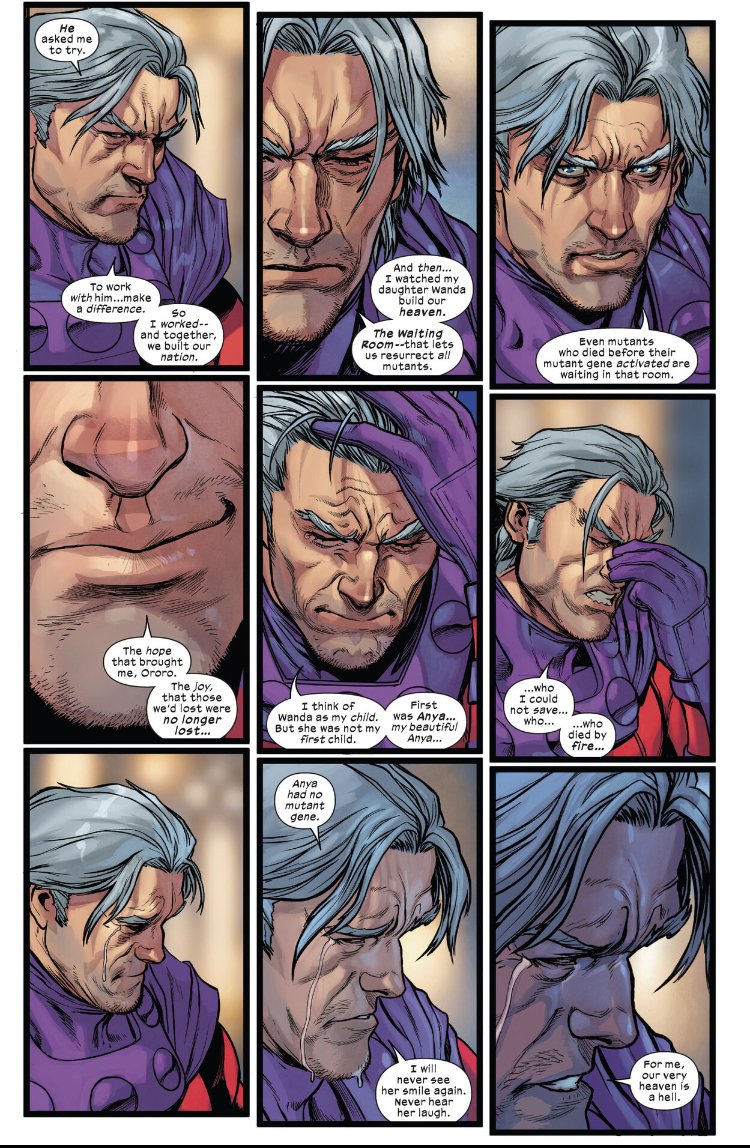

• Stefano Caselli, who has already done strong work on Marauders, SWORD, and Inferno, has risen to the occasion of Ewing’s plots. He’s very good with pacing and drama, and in depicting nuance in facial expressions. I was particularly impressed by a page in the third issue in which Magneto cycles through facial expressions in nine panels, his agitation subtly emphasized by the equally sized panels not neatly fitting into a grid.

• Federico Blee’s color art is essential to this series, his bright palette of mostly warm colors always signaling to the reader that they’re on a planet with a very light and atmosphere. He does a lot of work to make sure everything feels alien and surreal and geologically pristine, and maintains a sharp contrast with scenes set in the cold lighting of Brand’s space station or the more blue-green hues of Krakoa. It’s incredibly thoughtful work, something which ought to raise his profile as a colorist in the medium.

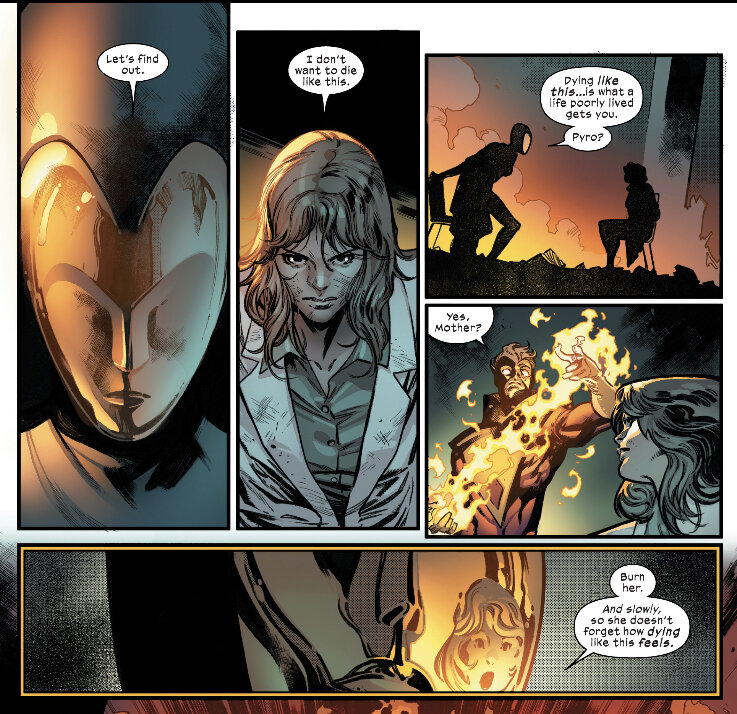

• The guest artists on the fourth issue are well chosen, and fit Ewing’s established MO from his past work on Immortal Hulk and Guardians of the Galaxy of making sure that shifts in art style are matched to shifts in narrative style. In this case, we get three vignettes on the theme of death before… well, we’ll get to that later. Juann Cabal and Andrés Genolet both do fine work in that issue, but I was most impressed by Michael Sta. Maria. I wasn’t familiar with his art before this issue, but I’d be quite happy for him to return to this book.