Welcome to Genosha

“Welcome to Genosha” / “Busting Loose” /

“Who’s Human?” / “Gonna Be A Revolution”

Uncanny X-Men #235-238 (1988)

Written by Chris Claremont

Pencils by Marc Silvestri (236, 238)

and Rick Leonardi (235, 237)

Inks by Dan Green (236, 238), P. Craig Russell (235),

and Terry Austin (237)

“Welcome to Genosha” is one of the most politically charged stories of Chris Claremont’s original 17 year tenure of writing Uncanny X-Men and its associated titles, and introduces the island nation of Genosha, which in retrospect is his last major conceptual contribution to the X-Men mythos. Genosha is a country which has quietly enslaved its mutant population for its economic gain, and have developed nightmarish brainwashing techniques that reduce mutants to docile, obedient workers who live only to use their powers to serve the state.

Genosha was clearly inspired in part by apartheid-era South Africa, but the severity of the situation was ultimately Claremont showing us a worst case scenario of how humans might treat mutants that’s as grim as the death camps of “Days of Future Past” but more plausible in the sense that it’s unlikely a capitalist system would prefer to exterminate a resource as potentially profitable as mutants. Genosha is, on a conceptual level, a dark reversal of Wakanda – whereas the latter fictional African nation is a sci-fi Afrofuturism fantasy of a black nation that was able to make major scientific achievements without the intervention of Europeans, Genosha’s advanced science is a direct result of exploiting mutant labor. The mutants of Genosha are collectively responsible for the existence of the high-tech weapons and processes that shackle them.

The story is a logical conclusion of a path that Claremont set his characters on starting with the “Mutant Massacre.” Under Storm’s leadership the X-Men became more ruthless and radical, and focused more on shutting down threats and pursuing justice for mutants than in promoting Charles Xavier’s dream of peaceful cohabitation of humans and mutants. Storm would never disavow those goals, but she was driven mainly by pragmatism and moral outrage. The Genosha arc tests the militancy of Storm’s X-Men – when faced with the absolute worst of humanity and a morally bankrupt society, what would they do? Would the X-Men actually overthrow a corrupt government?

Of course they would. But in doing so, the X-Men have to abandon their role as superheroes to become revolutionaries. Superheroes traditionally exist to prop up a status quo, and under Xavier’s leadership the X-Men’s goals were mostly focused on protecting a society that hated them in the interest of gradual assimilation. Storm’s X-Men have no interest in protecting a corrupt social order, so in this story Claremont can present a fantasy of extremely powerful minority figures smashing a system. The conclusion of this arc is all catharsis – the Genoshan state is shattered, the “mutates” are liberated, and the X-Men head back home in the end. It’s a satisfying conclusion, but it’s hardly the end of the story. A couple years later in “X-Tinction Agenda” we find out that Genosha was only briefly set back by the X-Men’s intervention and their violent actions only further radicalized their government. The X-Men can damage the system, but without the necessary tedious and difficult ongoing work of building a better society, the worst elements will persist.

This story marks the end of Claremont’s initial arc for Storm. He writes her out of the series for a little while after “Inferno,” and his last significant Storm story of his original run was a drastic left turn involving her being regressed to childhood. To some extent, the Genosha story represents what the X-Men ought to be – full-on revolutionary freedom fighters –but that role would be difficult to maintain in the format of a shared-universe superhero comic. Like, if the X-Men are going to overthrow Genosha, why not the United States too?

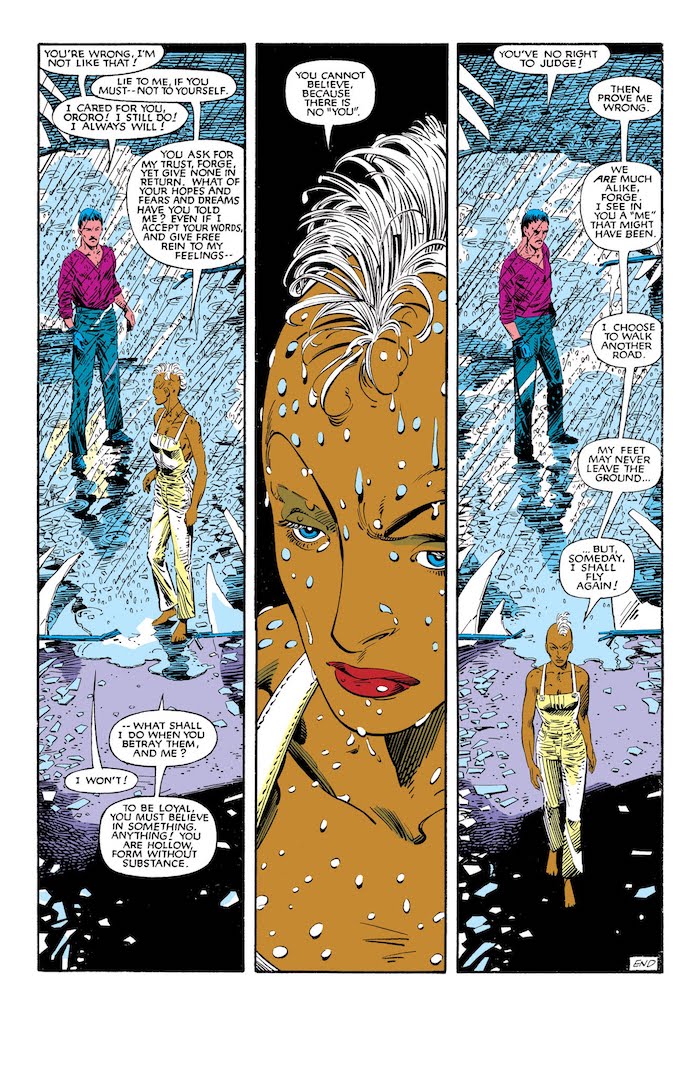

But this political radicalism is the appropriate end point of Storm’s leadership of the X-Men. She is not someone who is willing to let unjust systems stand, and will do whatever it takes to smash racist, patriarchal, and fascist capitalist states. It’s odd how much of this aspect of Storm has been erased in subsequent years – many writers forget her passion and “by any means necessary” approach, and while Cyclops took on a similar form of radicalism through this decade, every writer cast her as fundamentally opposed to these moves despite the number of major canonical Claremont stories that would suggest that she’d more likely look to his efforts and think “yes, finally.”

The Genosha arc was published bi-weekly in the run-up to the “Inferno” crossover, and as a matter of scheduling, was illustrated by regular series artist Marc Silvestri and recurring guest artist Rick Leonardi. Leonardi’s art is strong but has never been to my taste – there’s something about the contrast of roundness and scratchiness in his linework that has never been appealing to me. Silvestri, however, is one of my all-time favorite X-Men artists. He’s sort of an odd figure now – somewhere in the mid-90s his work severely devolved on a technical level, but through the late ‘80s he’s a top-notch draftsman with a rough but elegant style that pulls as much from classic fashion illustration as it emulates the grounded realism of old school Marvel artists like Joe Kubert and John Buscema. Silvestri’s men are grizzled and macho, and his women are rendered like pop stars and supermodels but somehow more beautiful. As idealized as his heroes get, his pages are rooted in recognizable settings full of average-looking people for contrast.

Claremont, always so good with playing to his artists’ strengths, gradually took the glossy sensuality of Silvestri’s artwork – along with the creative blank check that came as a result of Uncanny X-Men’s massive sales and the recent departure of micromanaging Marvel editor-in-chief Jim Shooter – as license to push the X-Men into explicitly horny territory. A large chunk of the Genosha arc is devoted to a subplot about Madelyne Pryor’s corruption and transformation into the vengeful Goblin Queen prior to “Inferno.” These pages, many of which take place in abstracted fever dreams, present Pryor’s trauma and rage but also her emerging extreme sexuality.

Claremont’s X-Men had always featured subtextual nods to his interest in BDSM and roleplaying but with Silvestri he was pushing it all to the surface. Pryor spends all of Inferno wearing an insanely revealing costume that’s deliberately trashy as a way to taunt and scandalize her ex-husband Cyclops. Cyclops’ brother Havok, who at this point is fully seduced by Pryor, ends up wearing even less – pretty much just a loincloth, and a fairly skimpy loincloth at that. Mister Sinister, who was designed by Silvestri, ends up looking like a leather daddy goth dom in this context. It’s wild stuff, and even more so when you consider that the overwhelming majority of the readership at the time – including myself – were children. I appreciate the subversive energy behind these comics, and respect the overwhelming horniness of it all. It’s certainly the work of eccentric individuals rather than sanitized corporate content. They were going waaaaay over the top at a time when comics were still mostly quite old fashioned in story and art, so it’s hardly a surprise that these issues sold in outrageous quantities relative to most anything else.