The New Testament Of Irene Adler

“All Mankind’s Woes”

“The New Testament of Irene Adler”

Immortal X-Men #2-3

Written by Kieron Gillen

Art by Lucas Werneck

Color art by Dijjo Lima (R.I.P.)

“All Mankind’s Woes” mainly serves to establish Hope Summers’ role in this story as she becomes the newest member of The Quiet Council thanks largely to the machinations of Exodus, who considers her to be a messiah. For the uninitiated, Hope was introduced in a 2007 crossover story called Messiah Complex in which she was the first mutant child born following the Scarlet Witch’s “no more mutants” hex in House of M. As a result many factions of mutants and anti-mutant forces took an interest in her, and Exodus was among those who believed her to be a messiah. She was brought to the future and raised as Cable’s adopted daughter – hence the Summers surname – and she looks like a young Jean Grey because for a long time she was heavily hinted to be a reincarnated Jean. She eventually made good on her messiah status by using the Phoenix to bring back mutants at the end of Avengers Vs. X-Men, but that now seems like a lesser work compared to Jonathan Hickman making her the leader of The Five, the group who have collectively made mutants effectively immortal and have resurrected thousands of mutants in a short span of time.

As you can see, Hope is a character with a lot of baggage. She’s also a character who Kieron Gillen has used extensively before, and he’s by far the writer who has done the most to make her a distinct person rather than a plot device. She was the star of his short-lived series Generation Hope, and was a regular cast member in his original Uncanny X-Men run. Gillen’s Hope is very much the pragmatic hard-ass Cable raised her to be, but she’s also a genuinely good and humble person who chafes at the adulation of people like Exodus. The second issue reestablishes all this in her actions – her power makes her thrive on teamwork, she’s decisive and ruthless in her plan to stop Selene, and she inadvertently repays her debt to Exodus by informing him that the extent of his power is determined by how much others believe in him. It seems like it probably won’t be a good thing that Exodus, a zealot with cult leader tendencies and omega level powers, learns this about himself. But I like the dynamic Gillen is setting up here – a political alliance, a budding friendship, two mutants who requires other people to make them powerful. It’s an intriguing way to explore the “cult of personality.”

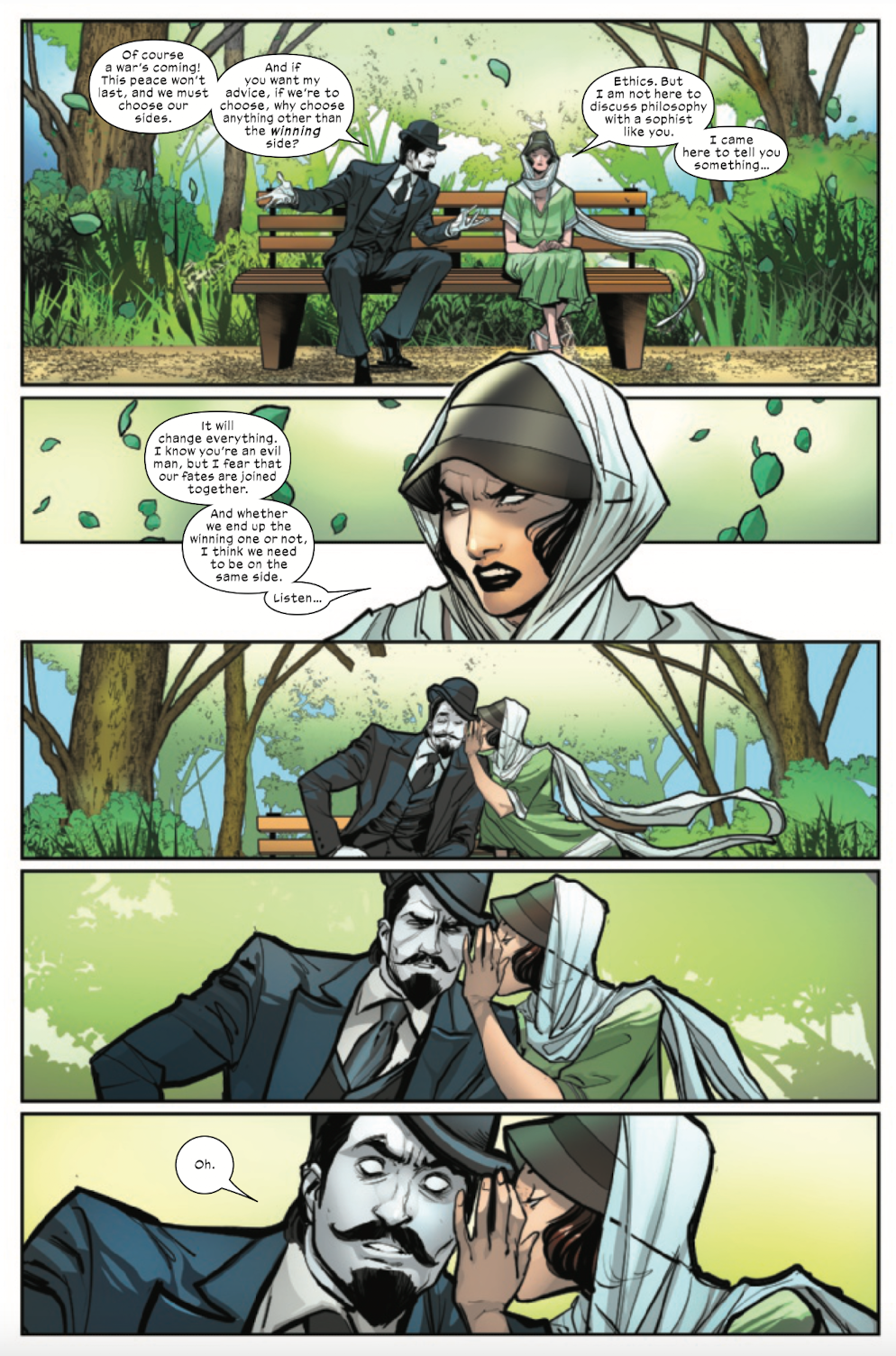

“The New Testament of Irene Adler” is Gillen’s deliberate echo of Jonathan Hickman and Pepe Larraz’s now classic “The Uncanny Life of Moira X” in House of X #2. That story set up Moira and Destiny as parallel figures, and so this time we get a look into Destiny’s life. Gillen is largely connecting the dots on what other writers have put down over the years – most especially the work of Destiny’s co-creator Chris Claremont – but he does some interesting work in fleshing out the character’s romantic relationship with Mystique, which was largely left to subtext and cryptic Comics Code work-arounds for the majority of her publication history. The most crucial bit of continuity surgery performed in this issue is explaining Destiny’s murder by Legion during Claremont’s original Uncanny X-Men run and how that connects to Hickman’s reinvention of both her and Moira. It all fits together perfectly though I suppose it was already implied by Hickman – Destiny was aware through her visions of the future that she had to die for the Krakoa project to happen, and in retrospect she understands that the reason was Moira’s intense fear of her.

Whereas the Moira story showed us paths Moira had already taken, this Destiny issue naturally gives us a glimpse of what may come down the line. Hickman and Gillen are both very sharp and deliberate writers, but the difference between them is best illustrated by the depiction of these things in text – Hickman gives us an elaborate timeline filled out with historical events, while Gillen gives us an abstract double page spread with events presented as evocative titles, like track names from an album or a catalog of Marvel trade paperbacks that have yet to be published. Hickman is concrete and meticulous like the scientist Moira, Gillen is artsy and lyrical and well-suited to the prophet Destiny.

There are three very important things established by Destiny’s flood of new visions of probable timelines. The first is her vision of Gillen’s forthcoming event AXE Judgment Day, and Destiny imploring the other council members to trust her visions in order to protect themselves from a coming Eternals attack. The second is that she becomes aware of Sinister’s use of cloned Moiras, which she deduces is the reason every timeline she sees cuts off abruptly, and this all emphasizes how high the stakes of this story are now that as she puts it, “the universe is a snow globe tossed between the hands of a gin-addled child.” The third is that every vision of the future Destiny has does not include Mystique, which is a nice reversal of Hickman’s “The Oracle.” Mystique only wanted to bring Destiny back, Destiny only wants to keep Mystique around. Both writers present these women as cold, calculating, ruthless self-described terrorists, but they really know how to make you root for their love.

• Speaking of Mystique bringing Destiny back, the third issue addresses Mystique’s conspiracy in Inferno in a Quiet Council meeting, which gives Xavier the opportunity to whine about the others nitpicking the decisions he, Magneto, and Moira had to make in order to create the nation of Krakoa. I empathize with him, but the self-pity and passive-aggression is very unappealing and exactly why so many of the other characters have come to loathe him. It’s a good character beat, and also gives us an interesting moment in which the always judgmental Kate Pryde admonishes him for being cruel to Mystique. The traditional X-Men members in the cast – Kate, Storm, Colossus, Nightcrawler – have largely taken a backseat in Gillen’s story thus far, and it’s just nice to see one of them voice an opinion that is not fully on the same page as Xavier.

• Lucas Werneck continues to impress, rising to the challenge of large scale action and montages of future events, while excelling at character expressions and body language in council debates. I’m fond of Werneck’s wide variety of line weights on any given page, ranging from the ultra-fine to thick chunky outlines to emphasize extreme depth of field, a bold figure placement, or a somewhat surreal effect. His page design also tends to feel loose and spacious, which helps to alleviate the density of Gillen’s text. It all comes out balanced rather nicely – issues that feel more generous with plot and detail than most other Marvel series, but with a visual style that makes it feel breezy rather than heavy.

• Oh right, there’s a vision of what Exodus can become once trillions of people feed him with their belief. Even with him going after and destroying an evil Sinister…seems bad! I’m very much looking forward to seeing more on this topic.