X Lives of Wolverine / X Deaths of Wolverine

X Lives of Wolverine #1-5

X Deaths of Wolverine #1-5

Written by Benjamin Percy

Art by Joshua Cassara and Frederico Vincentini

Color art by Frank Martin and Dijjo Lima

X Lives and X Deaths was sold as an interconnected set of miniseries in the mode of House of X and Powers of X that would move the story of the X-Men into a bold new, post-Jonathan Hickman era. It’s not that. It’s two somewhat concurrent stories with haphazard plotting that are forced to connect at the end, and one of them continues from Hickman’s story in such a sloppy manner that it lowers expectations for what it is to come. The story has its merits, but it does not deliver on what was promised and was not at all a good idea as the first move after Inferno.

The big problems of X Lives/X Deaths are rooted in the worst aspects of continuity in Marvel comics. The plot of X Lives is so steeped in continuity that it would be entirely incomprehensible to anyone who’s not read all the comics it’s referencing, and is only somewhat incomprehensible to me, a person who has read most of them. It’s actually amazing the degree to which Benjamin Percy makes this story impenetrable and unfriendly to new readers despite it being sold as a major event, which means it’s at least notionally a jump-on point.

It’s not just that Percy is leaning so hard on continuity. People write stories like this all the time that are nevertheless quite accessible to readers. Percy’s story assumes too much of the reader – that they’re up on the ongoing subplots of his X-Force series, that they’re invested in all the lore of the Krakoa era of X-Men, that they know a lot about Wolverine and his history – and does not provide anything to help orient anyone coming in cold. The story begins in medias res and barely establishes its premise in the first issue, and then never fully clicks together as it goes along. The plot just seems to move in circles, and doesn’t even really pay off Percy’s ongoing story threads with Mikhail Rasputin and Omega Red. In narrative terms it barely moves anything forward, it feels like a lot of action-packed busy work that is overly dependent on Joshua Cassara making it all look cool. (He does, you can count on him for that.)

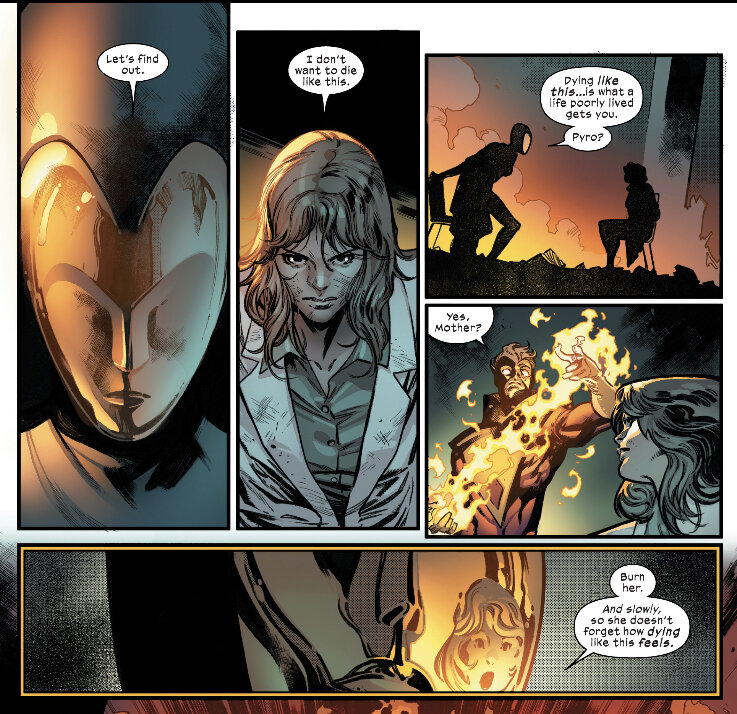

X Deaths is a different kind of bad continuity story, the kind that does not properly “yes, and…” someone else’s plot. This miniseries starts where Inferno #4 left off with Moira McTaggert running scared in Scotland after Cypher set her free through a gate one last time after Destiny and Mystique attempted to kill her. This is a very promising set up for the character, who is now powerless and alienated from the mutant nation she designed. Percy immediately adds a level of unnecessary peril – she’s got late stage cancer all of a sudden? – and then has Mystique hunting her down, even though that completely steps on the conclusion of Inferno, in which Cypher convinces her and Destiny to let her go and to focus on consolidating their power on the Quiet Council. It’s not out of character for Mystique to just do whatever she wants anyway, but this move signals that Percy cares more about his rather prosaic plot than having the ending of Hickman’s Inferno mean anything at all.

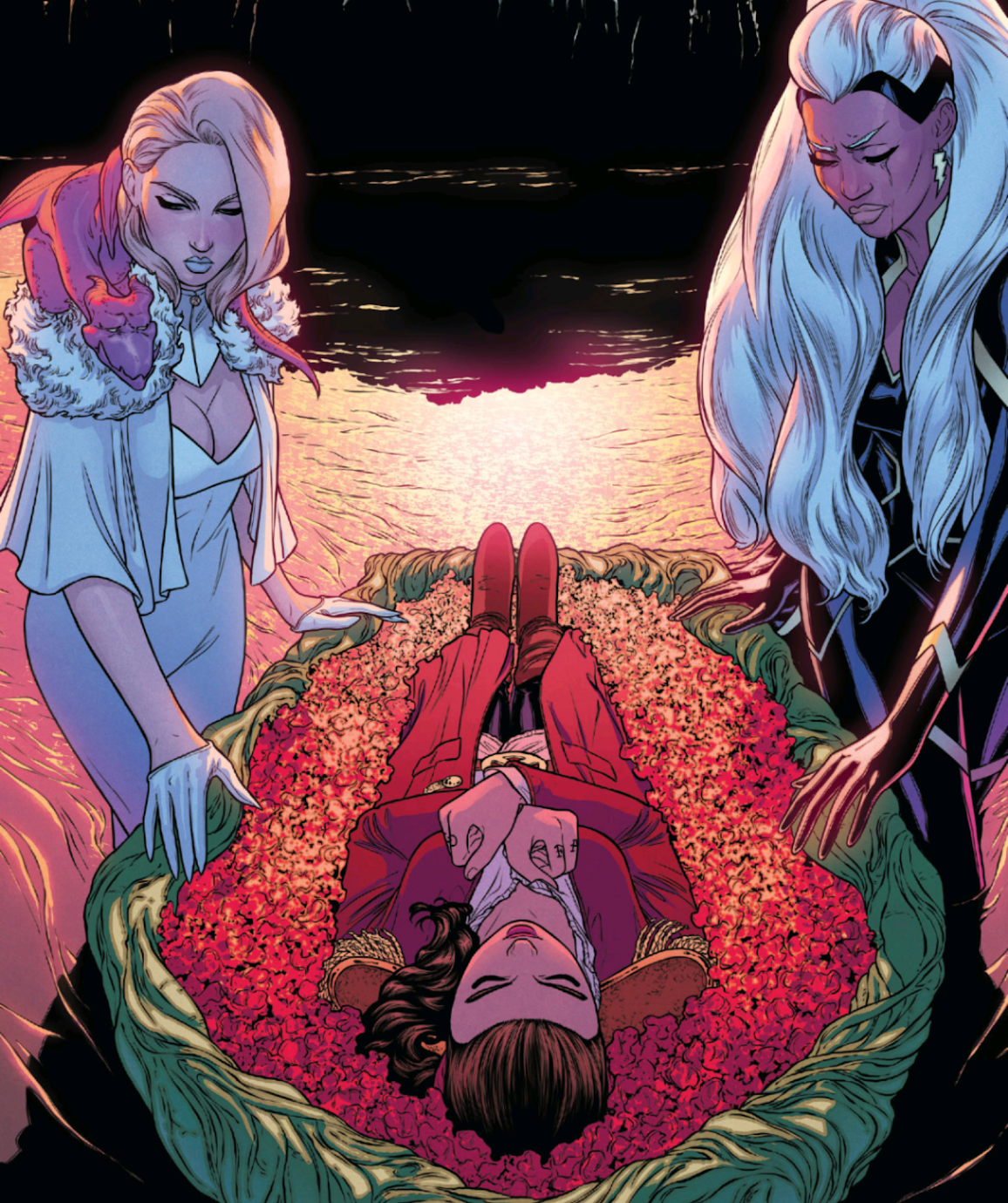

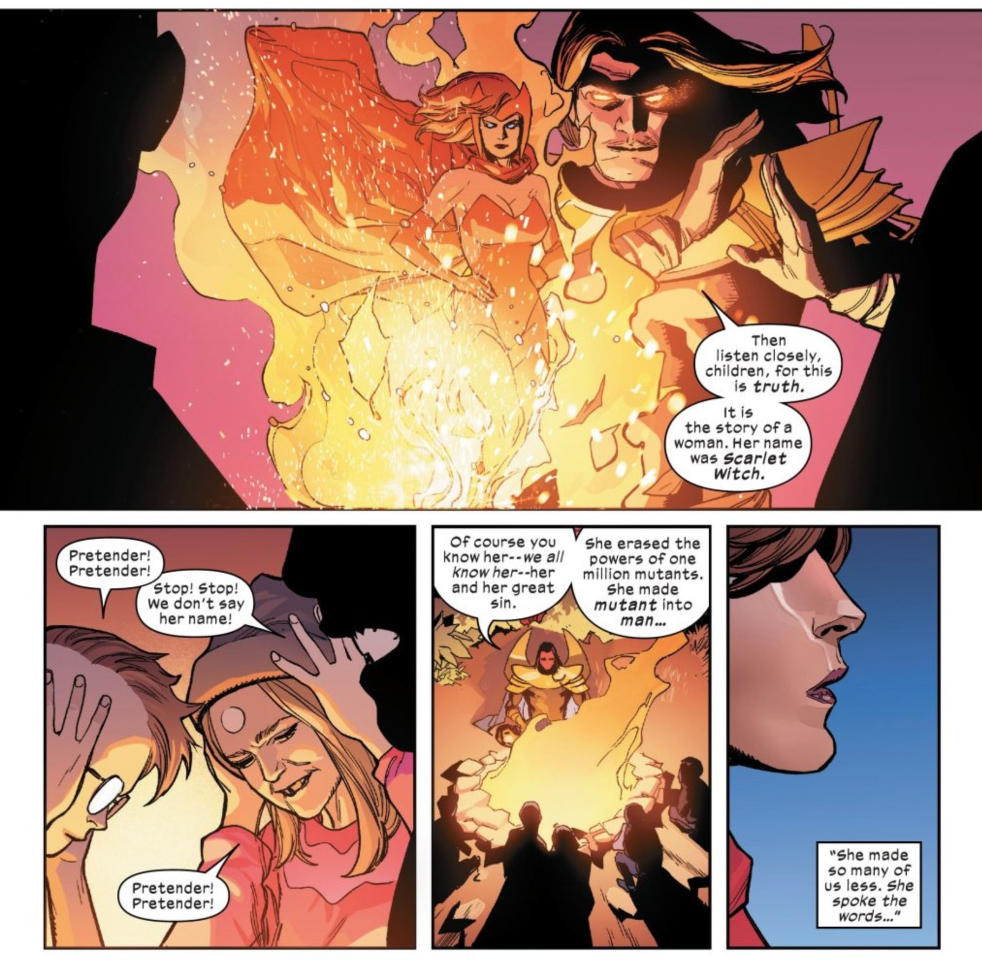

It gets worse for Moira from there. There’s some good on-the-run bits, but it’s all driving her towards a radical heel turn that doesn’t make sense with anything Hickman did with the character through his run. It makes emotional sense for Moira to feel betrayed, angry, and scared but the leap to “and now I want to wipe out the mutants” is nonsense. It’s a bizarre read on where Hickman left her, which was basically admitting that she still held on to the idea of wanting to “cure” mutants as a way of avoiding the same catastrophes over and over. She is not stating an agenda in Inferno, she’s being bullied by Destiny and Mystique because they have an awareness of why they killed her in her third life where she actively attempted to “cure” the mutants.

Percy makes the leap from the character’s nuanced emotional breakdown to interpreting it as a cackling supervillain masterplan. By the end of X Deaths we see Moira reborn as an AI bent on destroying the mutants, and this simply makes no sense given that this is the character who went through incredible lengths to create the Krakoan nation and was desperately afraid of AI as an existential threat. None of this makes emotional sense, none of it works logically as a story. It’s cheap and pointless. I naively thought we wouldn’t be going back to pre-Hickman messy storytelling like this so soon, but it’s in fact the very first thing that happens once the guy wrapped up and left. It does not bode well for what is to come, even if Kieron Gillen, Al Ewing, and Gerry Duggan all seem poised to do far better.

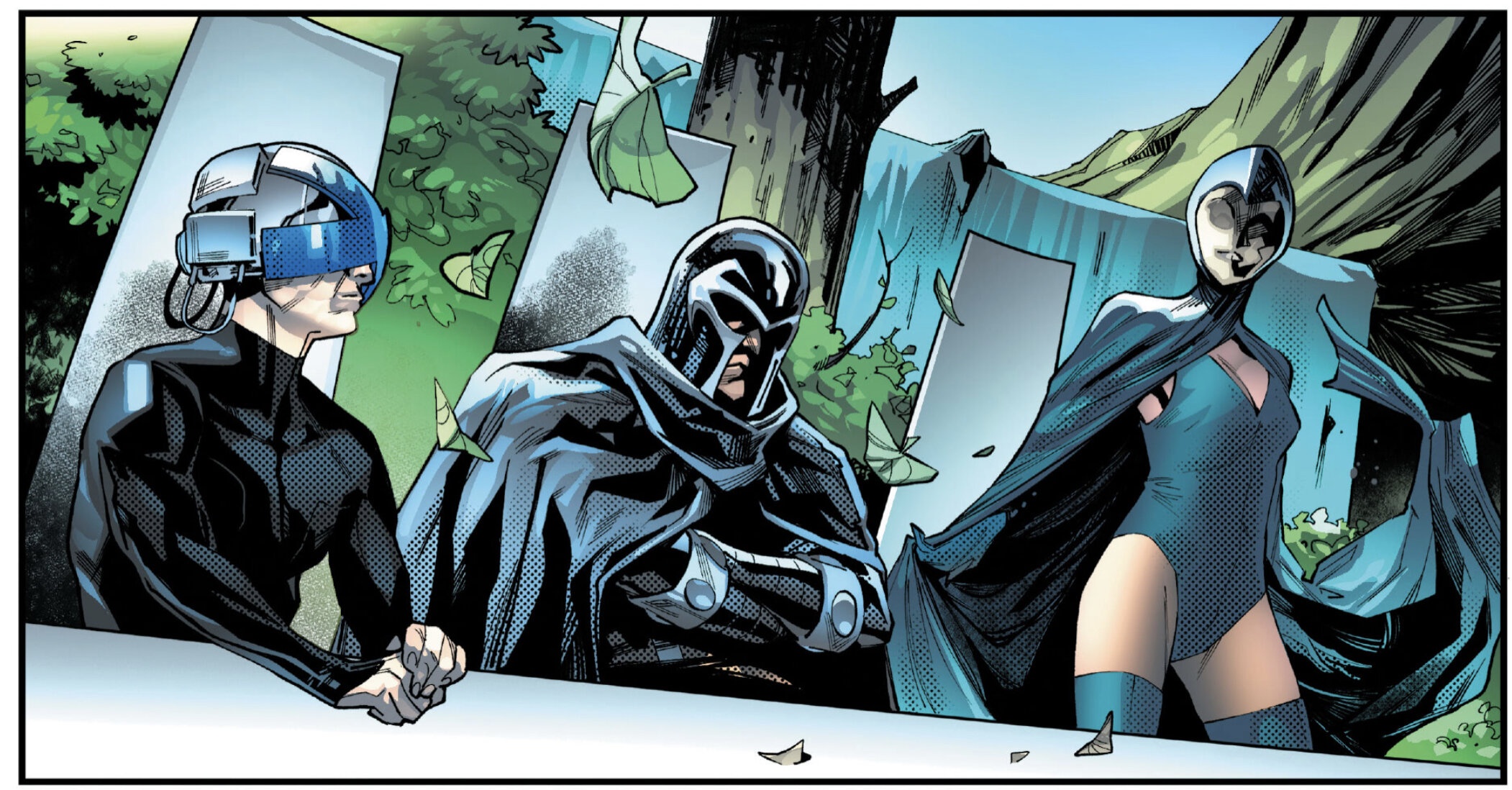

It’s bad enough that Percy has pushed Moira in such a ridiculous and awful direction, but in doing so he casually shot down a few plot beats that had potential to be much more thoughtful and interesting stories. For one, I’d been personally waiting quite hopefully for a story in which Moira’s ex-boyfriend Banshee learned the truth and was reunited with her, but when that happens in X Deaths it’s largely off panel and just set up for an outrageous and overtly psychotic bit of gore. There is a confrontation between Xavier and Moira in the fourth issue, but it’s so rushed and tossed off. We never got to see Xavier and Magneto learn what was happening with Moira in Inferno, nor will we get to see her get a meaningful conversation with them after it. It’s all just clumsily trampling on character beats in the interest of a plot that isn’t particularly thrilling or interesting.

Midway through the series Percy appears to add a clumsy retcon to Powers of X, something I figured would be somewhat off-limits and sacrosanct at least for the time being. Thankfully this is a misdirect, as we see in X Deaths #4 that Moira has somehow gone to the far future where Wolverine is in the same Preserve where he and Moira were kept by the Homo Novissima in her sixth life in Powers of X. It’s not the same one though, and the Phalanx’d-up Moira seems to have traveled to this spot in her 10th life with the goal of ascension. That Wolverine, now also Phalanx’d-up, heads back in time and… I guess prevents something at the end? It’s not super clear to me. At least the Phalanx’d-up “Omega Wolverine” looks cool. Federico Vincentini did a pretty good job drawing that version of the character, as did Adam Kubert on the covers. It’ll be a cool toy.

This story is baffling in so many ways, not the least of which is that up until this point Benjamin Percy has been a very good and disciplined writer on Wolverine and X-Force. I strongly suspect that part of the problem with this project is that the X Lives story was probably originally meant to run through Wolverine and/or X-Force, but got nudged up to event book status in the way that Chip Zdarsky’s concurrent Devil’s Reign event was originally just intended as a particularly eventful arc in Daredevil. The X Deaths end of things feels very wedged in at the last minute, likely out of editorial flop sweat wanting to lead readers directly out of Inferno rather than jump ship with Hickman, and needing to buy time before they could be ready to launch Gillen’s Immortal X-Men and Ewing’s X-Men Red. I’m giving Percy the benefit of the doubt here. I think this whole thing was rushed and pushed in weird directions as a result of outside pressures. I’m also willing to believe that Hickman was indeed fully on board with everything here with Moira, and that maybe he had intended to write it himself. But the slapdash nature of this series means that whatever Hickman had in mind has been put on the page in a way that is extremely unsatisfying, illogical, and confusing.