Season Of Change

Inferno #1

Written by Jonathan Hickman

Art by Valerio Schiti

Color art by David Curiel

Before reading this issue I had a feeling of vague dread about it, nervous that the end of Jonathan Hickman’s run on X-Men was premature and a bad compromise that kept more mediocre comics moving along while denying the promise of what we had been told was a long term three act story. I’m still a little sore about that possibility, but the first issue of Inferno is such a strong and exciting start to paying off plot threads started in House of X and Powers of X that whatever happens down the line, this story will probably feel like a satisfying conclusion.

Let’s just go scene by scene…

• The opening sequence calls back to the opening of House of X, but with Emma Frost reviving Xavier and Magneto. A cool bit of symmetry and foreshadowing. The cover of Inferno #2 seems to directly refer to this sequence, but given Hickman’s aversion to covers that spoil plot action it’s probably like how a few covers of Powers of X referred to plot from previous issues.

• The text pages updating us on Orchis’ aggressive advances in scale and the mutants’ failed attempts at attacking the Orchis Forge do a nice job of establishing that the stakes have been raised and many things have been happening since we left off from Hickman’s X-Men series. It essentially serves the same effect as the opening scrolls in the Star Wars movies, advancing plot that you don’t really need to see and throwing you into an action sequence set up by this information. This information also gives us a tiny pay off to Broo becoming king of the Brood, a plot point from X-Men that was probably intended for something bigger and more dramatic. Oh well, at least it’s not a total loose end.

• X-Force’s attack on the Orchis Forge introduces Nimrod and shows how easily it can dispatch mutants as formidable as Wolverine and Quentin Quire. This is another matter of establishing stakes, but more importantly it sets up the Orchis leads Devo, Gregor, and the Omega Sentinel trying to figure out how it is that they’ve been assaulted by the same mutants over and over again. Gerry Duggan’s X-Men series has been teasing at Orchis learning of mutant resurrection but this sequence is far more interesting in that their speculation is further off the mark – Devo is doubtful of the mutants making a scientific breakthrough – and not quite grasping the scale of what has been accomplished with the Resurrection Protocols. A lot of the tension in this issue comes from Orchis lacking a lot of information but having acquired enough data to be right on the verge of figuring out some potentially catastrophic things.

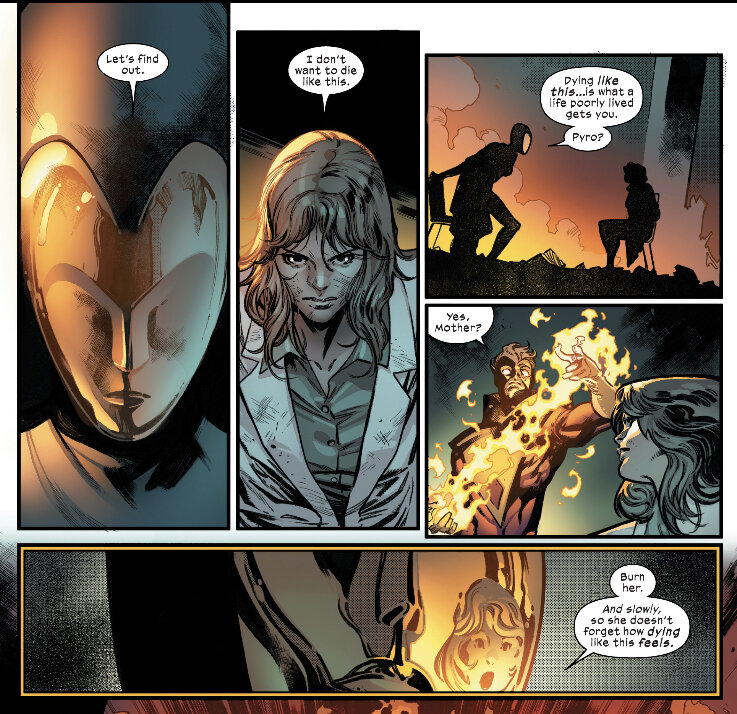

• We flash back to Mystique and Destiny confronting and murdering Moira MacTaggert in her third life, recreated by Valerio Schiti in a direct panel to panel copy of the memorable sequence illustrated by Pepe Larraz in House of X #2. Hickman has used this trick before, most notably in his Fantastic Four run in which Carmine Di Giandomenico redrew Steve Epting’s excellent scene depicting The Human Torch’s supposed death. The variance in the scenes comes on the fourth page in which we get some new dialogue from Destiny that we certainly could not have been privy to prior to later reveals in House of X and Powers of X. The ending of the scene has a significant change in dialogue that suggests that the Larraz and Schiti versions of this sequence are presented from different perspectives and memories – probably Moira’s the first time since that one focuses on her fear and pain, and Destiny’s in this one since it focuses more on her message and vision of the future.

• We see Moira in her present life, somehow holding the burned research book from her third life. Hickman and Schiti make a point of showing us this thing, which given our current understanding of how Moira’s lives work simply should not be possible. Hmmm.

• Moira’s movement triggers an unusual spike in Krakoan gateway activity that leads the Orchis network – which we see includes the ape scientists from X-Men #1 and Hordeculture from X-Men #3, two more random loose threads from the series that it’s nice to see in the mix here – to realize that Moira’s location is unique and presumably both important and deliberately hidden. The spike was likely caused by her use of a No-Space, a mutant technology that would be unknown to Orchis as well as nearly all living mutants. Hordeculture, who we learn has been instrumental in Orchis’ understanding of Krakoan biological technology, figure it out: Moira has two totally different portals. X-Force’s intelligence agents discover that Orchis is on to something, but you get the horrible feeling that this won’t be enough.

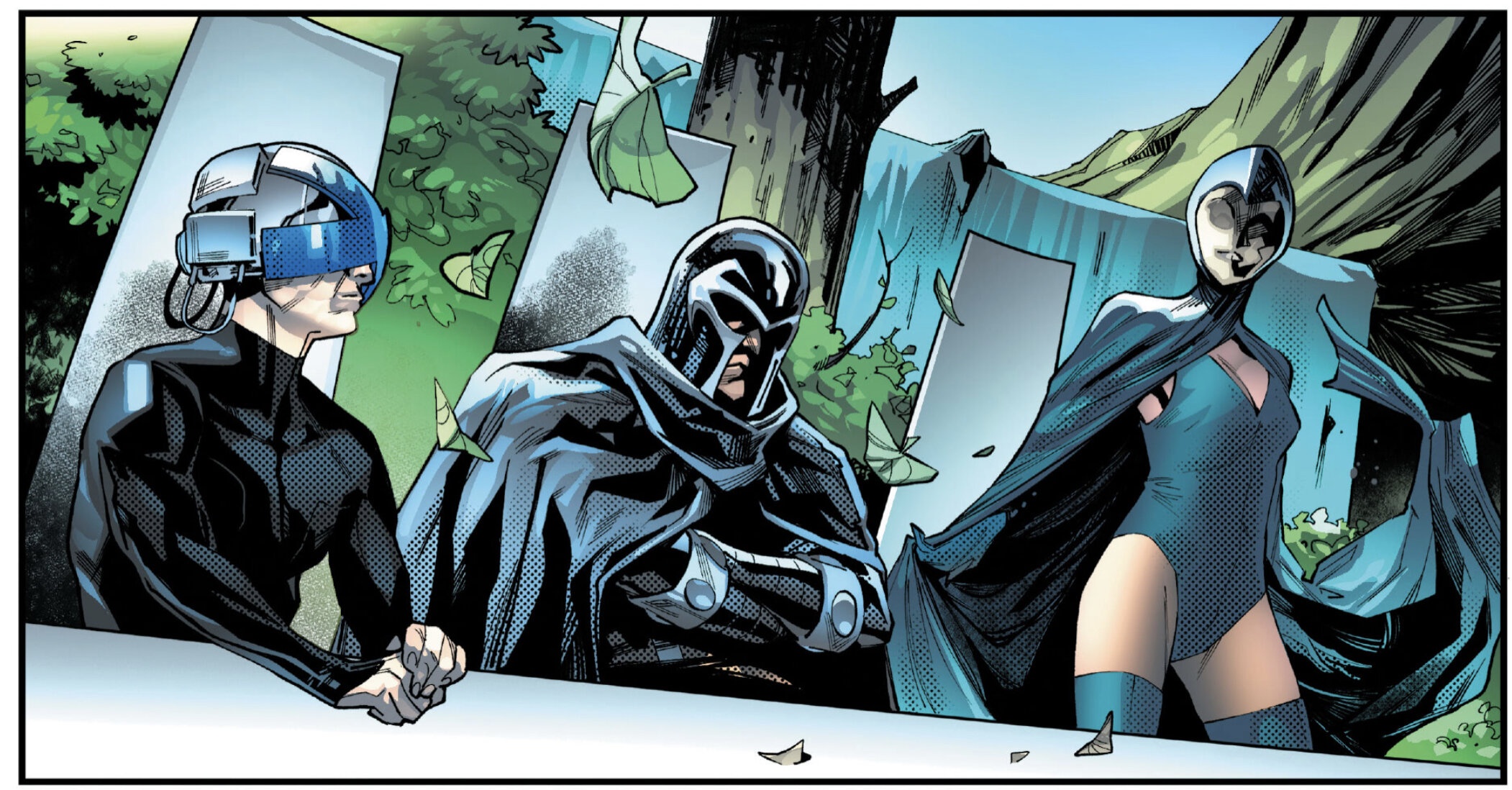

• Moira returns to her No-Space to be confronted by Magneto and Xavier, which gets a huge amount of exposition out of the way. Moira has become understandably embittered by her isolation, and resentful of these men have been surveilling her while also failing to stop the emergence of Nimrod. The crux of this scene is Moira reiterating that as she sees it, the two greatest threats to their mission are Nimrod and Destiny. She instructs them to use their knowledge and privilege to wipe out the possibility of her resurrection, which they appear to carry out separately. The sequence with Xavier collecting Destiny’s preserved genetic materials from Mister Sinister is presented quite ominously, with Sinister appearing even more Satanic than usual. This calls to mind the promise of his betrayal in Powers of X, in that he knows far more than Xavier realizes, and that Moira emphatically did not want Xavier and Magneto to form a partnership with him, aware of what other versions of Sinister did in her previous lives.

• A text page establishes that Black Tom Cassidy, whose powers allow him to commune with Krakoa’s living flora, has been suffering from seemingly psychotic episodes and dreaming of both being consumed by the island and machinery moving under his skin. This is an ominous lead-in to a scene with a rather chipper Cypher waking up to meet with his two best pals in the world – Krakoa itself and Warlock, a techno-organic creature related to the Phalanx. We see an echo of the sequence from Powers of X in which Cypher seems to infect Krakoan flora with the techno-organic virus, but this time it appears more benign. This panel – in which we see Cypher’s mutant hand, a living machine, and vegetation in apparent harmony – is also essentially another version of Black Tom’s nightmarish vision. File under foreshadowing.

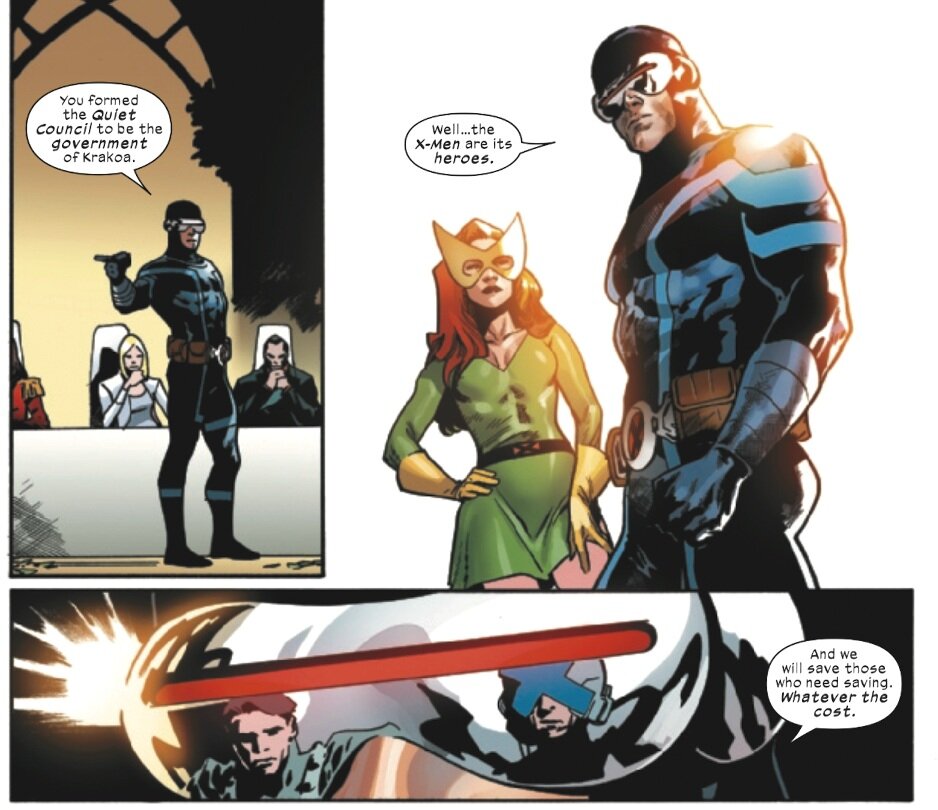

• We see a ceremony in which Storm coronates Bishop as the new Captain Commander of Krakoa, as Cyclops steps down from the position as lead captain. Cyclops will remain a captain, but Storm is surprised – “normally you’ve never given these things up without a fight,” a low-key nod to the classic Uncanny X-Men #201, which Hickman previously had Storm reference upon Cyclops’ resurrection in House of X #5. The scene also establishes Psylocke as Gorgon’s replacement and emphasizes the captains’ increasing independence from the Quiet Council’s supervision.

• The final scene is a Quiet Council sequence in which Moira’s urging to remove Mystique from power leads Xavier and Magneto to a rather ineffectual and wishy-washy suggestion to the rest of the council to consider the possibility of stepping down if they…like, want to, or something? It’s clear that they have not really thought this through, and Nightcrawler and Sebastian Shaw are particularly dubious of the proposition. This move entirely backfires as Mystique moves to replace Apocalypse’s seat on the council with…Destiny, who enters the council chambers very much alive. This startling cliffhanger is essentially Hickman’s equivalent to Grant Morrison’s Xorn reveal in New X-Men – “X-Men emergency indeed, Charles…the dream is over!”

But of course Mystique, a master of manipulation and subterfuge armed with the foresight provided by her dead wife, would be several steps ahead of Xavier, Magneto, and Moira. And all you need to do is look at the Winter table of the Quiet Council to glean how she pulled this off – Mister Sinister would have the means and the knowledge to tip her off, and Exodus has the telepathic power necessary to activate a Cerebro unit. Flash back to Magneto telling Moira of the composition of the Winter table – “it’s where we parked all of our problem mutants.” It’s also worth noting that Schiti’s art in the Quiet Council scene depicts barren branches and leaves falling from Krakoa’s trees. Winter has come.

(By the way, there’s a neat bit of symmetry in that Destiny seems poised to occupy the third seat on the Autumn table, and the corresponding seat on Arakko’s Great Ring is occupied by their precognitive mutant Idyll.)

And of course the specific things Moira was trying to avoid – Nimrod coming online and Destiny being resurrected – have come to pass in large part because her actions have either accelerated the timeline or forced the issue. And while Nimrod is an unambiguous nightmare, it actually remains to be seen whether or not Destiny will be the problem Moira fears or if she simply represents a threat of having her motives and methods undermined that’s more personal than structural.

Schiti’s work on this issue is some of the best of his career to date, and it’s clear that he’s done his best to level up to the demands of the story and to absorb some of Pepe Larraz and R.B. Silva’s stylistic decisions to keep a sort of visual continuity with House of X/Powers of X. Schiti does some outstanding work depicting facial expressions and body language – just look at Sinister’s delight upon Destiny’s entrance, and how Xavier’s body shifts from a defeated slump to a stiff and anxious posture upon seeing her. He also does nice work with Hickman’s recurring image of reflected faces, particularly Sinister’s ghoulish eyes on Xavier’s helmet and Xavier and Magneto on Destiny’s featureless and inscrutable metal mask.

• The title Inferno is, of course, repurposed from the major crossover event headed up by Louise Simonson and Chris Claremont in 1988. This is also obviously an echo of Hickman’s prior repurposing of Secret Wars for the finale of his Fantastic Four and Avengers mega-stories. The title suits the story in the sense that everything is about to burned down either literally or figuratively by a scorned woman – Mystique in this story, Madelyne Pryor in the original. But it’s also worth noting that the original Inferno was unique in that all of its story threads – the mystery of Madelyne Pryor, Magik and Limbo, Mister Sinister and the Marauders, X-Factor believing the X-Men to be dead – effectively concluded all major plot threads Simonson and Claremont had established starting around 1983. Maybe this establishes a tradition that can carry into future comics and the movie franchise: “Inferno” doesn’t have to be a particular story, but rather a spectacular crisis that pays off on years of plotting.