Creation

“Creation”

X of Swords: Creation

Written by Jonathan Hickman and Tini Howard

Art by Pepe Larraz

Color art by Marte Gracia

I’m shifting format slightly for this one, this is all going to be in “some notes” format.

• Pepe Larraz’s return to X-Men a little over a year after the end of House of X is as auspicious as it ought to be – the triple-sized opening chapter of a major crossover, as befitting an artist who has emerged as a defining – and more importantly redefining – artist on this franchise. Larraz’s pages here are top quality and play to his strengths in world-building and his raw talent for drawing evocative environments, nuanced body language, thoughtful page layouts, and perfectly paced and composed dramatic moments. It feels like a gift to read pages as well illustrated as this – the level of craft is above and beyond, particularly in a thing like the opening panel of the issue in which he effectively depicts a vast army with incredible elegance and economy of line.

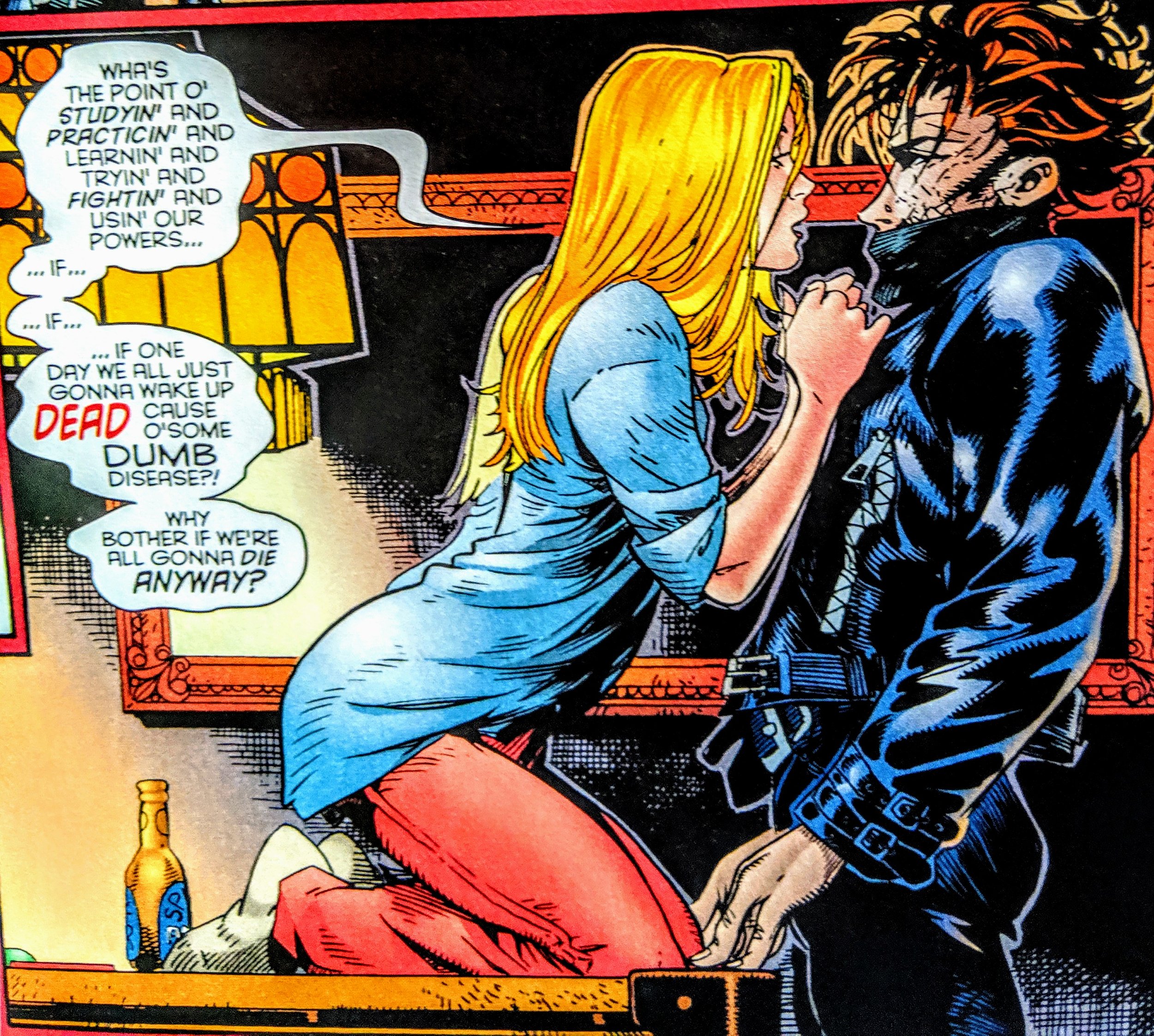

• The issue re-uses, recontextualizes, and in some cases alters the pages previously seen in the Free Comic Book Day special promoting this event. The tarot reading sequence feels right as the proper beginning of the story rather than merely a trailer for it, and I appreciate them using the obscure mutant Tarot’s interpretation of the cards drawn as a text page. It’s a clever bit of hand-holding for those of us who are either only dimly aware of tarot or totally ignorant. It’s interesting to note that the figures on The Hanged Man card have been changed somewhat – Banshee to Siryn, Glob to Rockslide, Trinary to Summoner – but I suppose that’s simply a result of plot revision.

• Archangel was mostly played as a joke in his Angel persona in Empyre: X-Men, so it’s nice to see him depicted more seriously in this story, where his extremely fraught relationship with Apocalypse is foregrounded to highlight that while he’s essentially the protagonist of this crossover the X-Men have a very bad history of being traumatized by him.

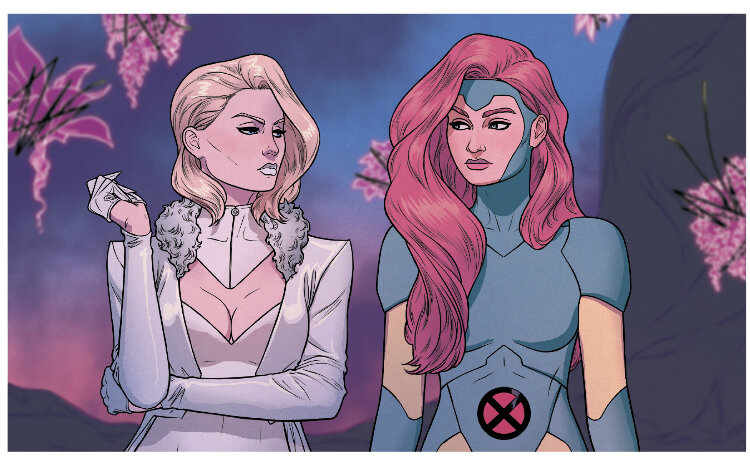

• It’s also nice to see Monet once again at the forefront of a story, as she drives much of the action plot in the second half of the issue in which the X-Men confront Saturnyne. Between this, House of X, Empyre X-Men, and Giant Size X-Men: Storm, Monet has been positioned as a major X-Men character and this makes a lot of sense – she’s a character with a big personality and a diverse list of extraordinary powers, making her an obvious person to place on the front lines of any battle. I like the way the typically haughty Monet is set up as a foil to the even haughtier Saturnyne here, and her casual mention that she’d be interested in taking Saturnyne’s job at some point. Maybe that’s just a funny line, or maybe it’s foreshadowing – we’ll just have to wait and see.

• In the lead-up to X of Swords we were led to believe that Apocalypse was the one pulling all the strings, but as we see in this issue he’s been manipulated just as much as he’s been manipulating the mutants of Krakoa. His Caesar-esque betrayal by Summoner and his the Horsemen is hardly a surprise but still hits with some emotional resonance and we’re fully aware of what a crushing disappointment this is for Apocalypse after centuries of waiting to be reunited with his lost family. And of course, at the end of this issue we see that Saturnyne has been playing everyone all along, and has set up a conflict for her amusement or potential gain in which he’s only just a pawn. It looks like a big part of this story will be Apocalypse being forced into true humility.

• At least a third of this story is rooted in the Captain Britain mythos developed by Alan Davis, Alan Moore, and Chris Claremont in the 1980s – most obviously the presence of two Captains Britain in Betsy and Brian Braddock, but also Saturnyne, the Starlight Citadel, and Otherworld. The map of Otherworld is intriguing, with references to expected characters like Jamie Braddock, Roma, and Merlyn, but also a few somewhat unexpected characters from this mythos like Mad Jim Jaspers and The Fury. The most surprising thing here is the suggestion that the missing all-powerful omega mutant Absolon “Mister M” Mercator is most likely the “unknown” regent of a realm called Mercator.

• The biggest curveball in this opening chapter by far is the revelation at the end of the issue that somehow S.W.O.R.D., the intergalactic intelligence agency created by Joss Whedon and John Cassaday in Astonishing X-Men, is somehow part of Saturnyne’s scheme. I can barely even speculate on how that fits into all this with Arrako and Amenth and Otherworld, but I like the feeling of having no idea where this plot is going.

• As the issue ends we learn that the macguffin driving the plot of this crossover will be some kind of tournament between the swordbearers of Arrako and Krakoa, and we’re given the name of ten swords that will be wielded by X-Men who’ve been indicated on either the Ten of Swords card in the reading early in the issue or the covers of forthcoming issues.

Some of the swords are obvious – Magik possesses the Soul Sword, Cable recently acquired The Light of Galador in his solo series, Cypher is bonded with Warlock. The Sword of Might would be Brian Braddock and the Starlight Sword would be Betsy Braddock. Skybreaker would be for Storm and The Scarab would be for Apocalypse given their respective themes as characters. Gorgon has a history with Grasscutter and Godkiller in previous Hickman comics, and I would assume Magneto would take the latter if just for the pompous name. Muramasa, a blade infused with Wolverine’s soul, is obviously meant for him, which is troubling as that one also appears as the 11th sword of Arrako. Hmmm.