Supernovas

“Supernovas”

X-Men #188-193 (2007)

Written by Mike Carey

Pencils by Chris Bachalo (188-190, 192-193) and Clayton Henry (191)

Inks by Tim Townshend et al (188-190, 192-193) and Mark Morales (191)

Mike Carey is one of the most prolific X-Men writers, having written 72 issues of X-Men and the original graphic novel X-Men: No More Humans. In that span of time he was a primary author of two major crossovers, “Messiah Complex” and “Second Coming,” and the sole author of the “Age of X” event. His tenure is easily overlooked, mainly because he’s never at any point the main writer on the franchise. His run begins as a relaunch alongside Ed Brubaker’s Uncanny X-Men while Joss Whedon and John Cassaday slowly published the second half of their best-selling Astonishing X-Men series. After “Messiah Complex,” his book – long the co-flagship of the line – is retitled X-Men: Legacy and becomes a Charles Xavier solo title. Once that story runs its course, it shifts into a Rogue solo series. These periods have their moments, but it’s mostly a lot of inconsequential stories that are often mired in a lot of continuity baggage. Carey not having a set team of characters to work with freed him to follow his muse and go deep on Xavier, Rogue, and Magneto, but also damned his book to seem very much like an extra X-Men title published for die-hard completists rather than an essential series.

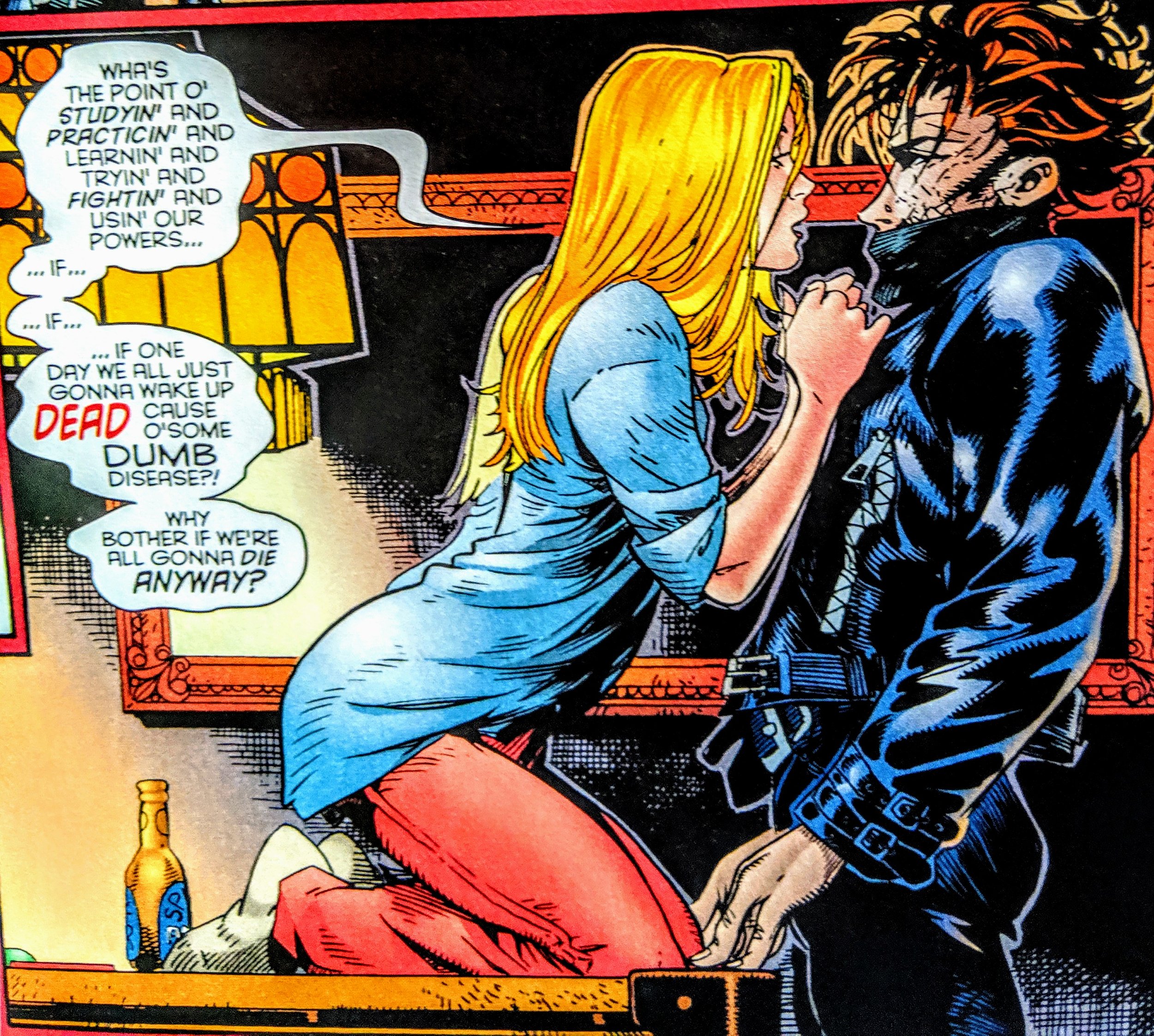

Carey started very strong though. “Supernovas,” his opening arc, is a showcase for his focus on thoughtful character beats, hard science fiction, and deep-cut X-lore. The story follows Rogue as she’s tasked by Cyclops with creating her own team to specialize in responding to crises while a lot of the other X-Men are either focused on running the school or off in outer space. Rogue is a deeply strange character to be given a leadership role, and that’s a lot of the point here. She’s a veteran, sure, but she tends to be a reckless loose cannon. Cyclops chooses to see her chaotic tactics as “inspired improvisation” in Carey’s first issue, and the remainder of his initial run up through “Messiah Complex” is essentially a referendum on the pros and cons of Rogue’s approach to leading a team.

Generally speaking, it does not go well for her, pretty much from the start. Rogue’s team is a ragtag assortment of characters, some of whom are close friends – Cannonball, Iceman – but the rest are mostly antagonists she needs to keep on a tight leash – Mystique, Sabretooth, Lady Mastermind – or random people who just happen to be on hand, like Cable and Omega Sentinel. It’s more of a cast than a team, but Rogue tries to hold them together as much as she can despite half the characters actively working against her goals.

Carey’s selection of characters set up a lot of good drama, but also highlight his intriguing approach to the very concept of a “team book.” He’s essentially making lemonade out of lemons – he didn’t have the option to have a more standard X-Men team, so he instead assembled an unlikely group of characters who are set up to fail. Most superhero team stories are built on a fantasy of people working together in harmony, but Carey is curious about what happens when that’s not an option.

The story also plays on one of the central themes of Rogue’s overall character arc – she is a reformed villain who became an X-Man after a brief stint in her foster mother Mystique’s Brotherhood as a teenager. She’s invested a lot in the idea of redemption, but is aware that it’s a bit too much to expect of a sociopath like Mystique and a full-on psychopath like Sabretooth. Over the course of this run, Carey asks the reader to be as optimistic as Rogue is trying to be about all this, but in the end he’s quite honest about the nature of the characters he’s working with. Rogue’s haphazard team-building only leads to betrayal and failure, and while that’s not entirely her fault, it very much is a story about how not everyone is cut out for leadership.

“Supernovas” is mostly illustrated by Chris Bachalo at one of his creative peaks. Bachalo’s work is highly distinctive but also constantly mutating, and this story comes at an intriguing point in his evolution where he’s increasingly drawing with color in mind and sometimes coloring his own pages. (The remainder is colored by Christina Strain and Antonio Fabela, who turn in some lovely work.) Bachalo has gone through some phases of strange, cluttered page designs but at this point he’s loosened up quite a bit and allows for a lot more negative space to be filled by ambient colors. One of his best narrative tricks for big dramatic moments here is to drop out backgrounds entirely in favor of large expanses of white space on the page, such as the aftermath of one of Rogue’s risky moves in the first issue, or a particularly creepy page in which a brainwashed Northstar appears before his suicidal twin sister Aurora in the second issue.

Bachalo did not draw the fourth issue of this storyline, likely due to scheduling problems. This is to be expected with monthly superhero comics, but this is a case where having a fill-in artist totally wrecks the specific atmosphere and aesthetic of the primary storytellers. Clayton Henry isn’t a bad artist but his bland traditionalism is jarring and breaks the spell of Bachalo’s designs. The switch to his pages is roughly equivalent to watching a Star Wars movie in which all of the cast is inexplicably replaced by soap opera actors and all of the production values drop to student film level for 20 minutes before going back to normal for the last 40 minutes of the picture.

Henry’s art disrupts the mood and drama, and his drab and unimaginative style actively undermines Bachalo’s designs for the story’s antagonists, the Children of the Vault. This group of characters, who were created by Bachalo and Carey, are not mutants but instead the result of the standard human genome being artificially evolved over a period of 6,000 years in a temporal accelerator. Carey was exploring the evolutionary biology concept for genetic drift and Bachalo was having fun with a set of characters who are meant to seem even more eerie and inhuman than the mutants. Henry’s interpretation follows Bachalo’s designs but makes them all look rather…literal. In context, it all just looks like bad homemade costumes, with all the visual poetry of Bachalo’s art removed. This problem of translating Bachalo’s work to other artistic styles probably explains a lot of why these characters have rarely been seen again outside of a follow-up storyline by Carey late in his tenure.