The Last Dream of Professor X

“The Last Dream of Professor X”

Powers of X #1 (2019)

Written by Jonathan Hickman

Art by R.B. Silva

Color art by Marte Gracia

Last week in House of X we were presented with a new status quo for mutants in which Charles Xavier gave them a homeland in the form of Krakoa, and they were poised to inherit the world within two decades. For the first time in ages, the future was bright for the X-Men! But here we are one week later in Powers of X #1, and we are confronted with the notion that just because nature dictates a mutant future, humanity can still intervene and change course in a genocidal act of self-preservation. Bleak visions of the future are a big part of X-Men mythology, but the futures presented in Powers of X may be the most upsetting yet if just because they are contrasted with the radical optimism of Krakoa and the potential of a mutant planet. It resonates with our moment in history too much for comfort – the threat of seemingly inevitable progress kicking oppressive forces into overdrive as the powerful desperately cling to their position.

Jonathan Hickman pulling the rug out from under us straight away focuses the story on the central theme of X-Men: The dream of a better world, and the nightmare of what happens if the dream is not realized. In what is effectively his second issue, he’s established the stakes of his X-Men. The story, particularly the sections that are presented as historical texts, reveal that the establishment of the Krakoan nation state sets in motion a battle between mutants and humans – and their machines – that’s not resolved for hundreds of years. Dr. Alia Gregor’s forecast of mutants becoming the dominant species doesn’t turn out to be the case. 100 years later and there’s just 10,000 mutants left and almost all of them are living in Shi’Ar space. It’s heartbreaking.

Powers of X tells a story in four time periods: The very beginning of the X-Men, the present tense of the X-Men ten years later, the remaining X-Men of 90 years from now, and the distant future of the X-Men in their 1000th year. The pages set in the present mostly move along a bit of plot with Mystique carried over from House of X and allow for a bit more time with the current Xavier, though he’s no less inscrutable than he was in House of X. This scene is mostly interesting in setting up a question of what exactly Mystique has stolen and brought back to Xavier and Magneto, and for establishing that Hickman has a good handle on Mystique, a woman who is always working in her own interest and is constantly running some con or another.

The oblique opening scene set in the past is the most fascinating bit of a rather dense and eventful issue. The young Charles Xavier is confronted on a park bench by Dr. Moira MacTaggert, who speaks rather cryptically but reveals that she knows him rather well though he believes he is meeting her for the first time. This is a puzzling moment for longtime readers as it is long established that Moira and Charles were once young lovers and that she was a crucial figure in helping him establish the X-Men. The scene ends with Moira inviting a confused Charles to read her mind, and with his surprise at what he finds there. We won’t know about what he sees in her head for at least another week or so.

Something is off about Moira. That much is signaled in the moments just before Charles sees her, as he looks up to the sky and watches birds circling overhead – traditionally a bad omen that can signal a coming storm, or the hunting of prey. Moira’s tone is knowing but ambiguous, and she is coming to Charles just after his great epiphany about “a better world and my place in it.” Her timing seems rather deliberate. Is Moira a predator of sorts here? Is Charles her mark, or a patsy?

Moira’s most cryptic dialogue accompanies images of three tarot cards which are illustrated with images of characters and settings from the X-Men’s 100th year, which make their proper debut a few pages later.

I have minimal knowledge of tarot, but crowdsourced a reading of these three particular cards on Twitter and every interpretation was about the same. Here’s a few of the ones I found particularly resonant with the themes Hickman is laying out with regards to Charles Xavier:

you're absolutely positive about a course of action, but it's going to lead to a major shakeup in ways you didn't expect and will be uncomfortable (this doesn't mean don't do it). don't rely on substances/sex to get you through, they will make the discomfort worse. https://twitter.com/noradotcool/status/1155939469582721024

my read would be the magician is the path you wanted, the tower came in and shook everything up radically, and the devil is how you deal with the aftermath, probably you've been indulging in some harmful behaviors and need to stop to keep moving/heal. https://twitter.com/cortneyharding/status/1155951708284968960

Pride goeth before the fall, which you know, but you just can’t help yourself https://twitter.com/redrawnoxen/status/1155937015809970176

The magician is the goal

The tower what needs to fall for that to come through

The Devil the catalyst for the next transformation https://twitter.com/henrydarthenay/status/1155944493125758976

It seems likely Hickman is establishing the primary theme of Xavier’s arc not just for House of X and Powers of X, but for his entire run to come. The goal, the obstacle, and what must be done to overcome it. So…is Xavier’s plan with Krakoa in the present the goal, the obstacle, or the catalyst for the next transformation?

A century later things have gone terribly wrong. Hickman and artist R.B. Silva present a vision of the future that borrows thematic and visual elements from the most famous dark timelines of the X-Men’s past – “Days of Future Past,” “Age of Apocalypse” – but mostly feels fresh and distinct. The X-Men of this era are vaguely familiar – entirely new characters who look like mash-ups of classic characters. Hickman relies on historical information in text pages to establish the backstory of this future and keeps the story pages focused on emotion and action. Long story short: We’re in the last days of a war between the Man-Machine Supremacy and what remains of the mutants, and these X-Men are the product of a breeding program by Mister Sinister that goes horribly wrong, mainly because the mutants decided to trust their future as a species to a Machiavellian mad scientist who calls himself Mister Sinister.

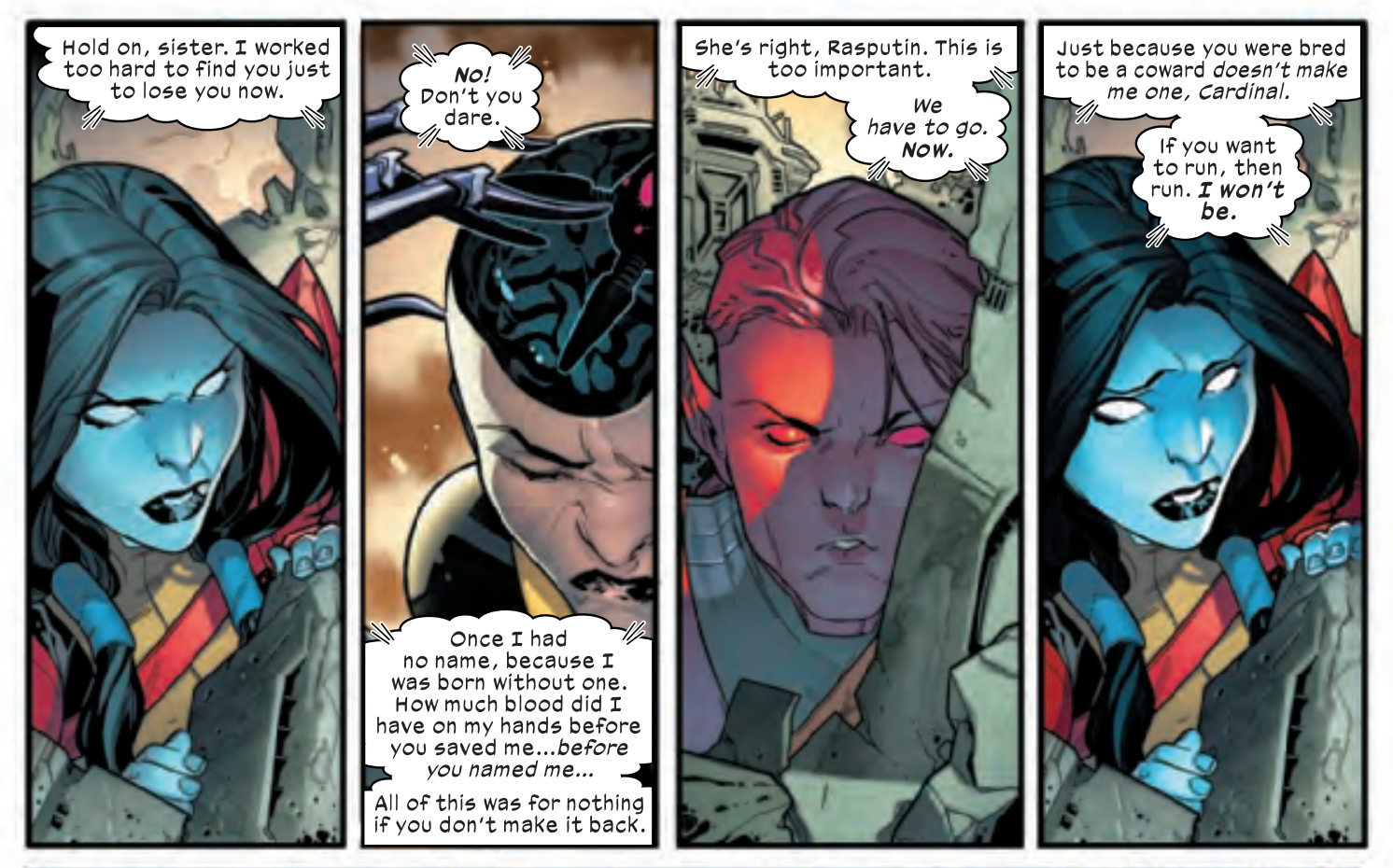

Our three main characters in this era represent three forms of bred mutants. Rasputin is a Chimera class mutant, a nearly unstoppable being made from the combination of Colossus, Kitty Pryde, Quentin Quire, Unus the Untouchable, and X-23/Wolverine’s genes. Cardinal, basically a red Nightcrawler, is an Outlier, a mutant designed for war who nevertheless developed spiritual and pacifist tendencies. Cylobel is a hound with an unreadable “black brain” bred by the Man-Machine Supremacy to infiltrate and betray her own kind. Cylobel is captured by the machines and brought to their leader, Nimrod the Lesser. Cylobel’s programming backfires on her masters – she has betrayed them, and not the X-Men. Her last act before being deposited into a system that will break her body and mind down to nothing more than data to be processed in the interest of further understanding “the mutant anomoly,” is an act of defiance. She embraces her martyrdom and swears that even if it takes “a thousand years,” mutants will endure and wipe out their oppressors.

Hickman’s Nimrod is delighted by her spunk. This version of Nimrod resembles the character created by Chris Claremont and John Romita Jr but has the personality of an effete elite who masks their inhumanity in politeness and shallow declarations of empathy. In addressing Cylobel, Nimrod prefaces extraordinarily cruel statements and actions with effusive apologies. You immediately recognize this guy. You’ve read his op-eds. You’ve seen him on cable news. He’s what happens when polite society is built on systemic injustice that stops looking anything like cruelty to the people on top. Nimrod doesn’t hate the mutants, he pities them! He is so sorry they are not at his position in the hierarchy. It’s so sad they must be killed! Silva draws Nimrod as a pastel behemoth with broad and cartoonish mannerisms not too far removed from the cute and cuddly Baymax in Big Hero 6. The design is just a tweak on Romita Jr’s original look, but it’s smoothed out a bit so he looks more like an Apple product. He’d make a great stuffed doll.

Cylobel may have accidentally predicted the future with her “a thousand years” line. In the issue’s final scene we’re a thousand years from the day Charles met Moira, in the era of “ascension,” and meet a bald blue humanoid called Librarian who is attempting to recover information from Cylobel’s preserved body in Nimrod the Lesser’s archive. The Librarian is accompanied by a small drone – Nimrod the Greater. This scene is rather oblique, but ends with two important bits of information: The “human-machine-mutant war” has ended in a surprising way, and the current residents of Earth have kept some remnants of humanity in a place called The Preserve. The issue ends with a shot of a man and woman lurking in The Preserve in shadows. They look a bit like…Mystique and Toad?

A few stray notes:

• In the tarot sequence, the magician card is Rasputin and the devil card is Cardinal. This makes some sense in that context, but I’m more intrigued by the way these two characters essentially split the spirit of Xavier’s ethos in half – one represents the idealistic fight, and the other the dream of peace. Rasputin is bred for war, but Cardinal retains too much of his ancestor Nightcrawler’s spirituality to embrace the potential of his weaponized genes.

• Much in the way that Pepe Larraz stepped up his game in House of X, R.B. Silva reveals the full extent of his talent in this issue. Silva has been working on X-Men comics for the past couple years but has mainly been working on rather bad material – he drew a good chunk of the absolutely dire X-Men Blue/X-Men Gold series written by Cullen Bunn and Marc Guggenheim. But whereas those comics were largely exercises in rote continuity mining and pointless nostalgia, Powers of X gives Silva the opportunity to create, and a lot of the energy of this comic comes from his obvious delight in designing his own world. You can see the influence of modern video games as well as traces of Joe Madureira’s designs from “Age of Apocalypse.” He also integrates the particular geometric elements of Chris Bachalo’s design for Omega Sentinel in that character’s descendent here without compromising his aesthetic identity. There’s still a good amount of Stuart Immonen influence in Silva’s art, but that’s receding as Silva asserts his own identity with crisper, cleaner linework that leaves more of the lighting effects to colorist Marte Gracia.

• This issue gives us our first look at a “No-Place,” which was mentioned in passing in House of X #1 in the text page outlining the use of Krakoan fauna for mutants. A “No-Place” is a Krakoan habitat that exists outside of the Krakoan collective consciousness and is created by an artificial Krakoan flower. The No-Place, a zone that should not be, is depicted as dark and upside-down to great, mildly unnerving effect.

• Charles Xavier seems to have developed telekinetic powers in the present. He has canonically only ever been a telepath.

• All four sequences of this story involve an attempt to access forbidden or lost information, but we do not know what that information could be or why it is needed. The story threads in the present and in year 100 leave off with emissaries passing off information to their superiors – in the case of Mystique, to Xavier and Magneto, and in the case of Rasputin and Cardinal, to a superannuated Wolverine and the remnants of the X-Men.

• The heavy themes around betrayal in the future sequences of this issue suggest Moira and Mystique are not to be trusted in the past and present. (Of course Mystique is never to be trusted.)